Artists Represented by Warmun Art Centre

With text by Tristen Harwood

Warmun Art Centre in the East Kimberly is connected to the old house I lived in with my nana, mum and my six younger brothers by single a 3000-kilometre road.

A proclamation of settler-colonial conquest: The Great Northern Highway. The road yawns over land from Perth to the state’s northern-most port, sun blooming in the distance like it’s not going down for weeks, so that as you’re driving the bitumen gently dissolves beneath you and you’re not travelling horizontally, but toward the sky.

In a survey of the East Kimberly Painting Movement (2013), Arnaud Morvan notes that paintings from the region: ‘can mix a planar perspective and a lateral view…’ and things ‘can be depicted from several angles at once.’ The visible and invisible, the intuitive and empirical features of emplacement decompose in large blocks of ochre – material from the places that are depicted – and coalesce into a kind of topological field. But topography is an insufficient term to describe what’s conveyed in East Kimberly painting practices.

The painted surface isn’t a fixed ‘landscape’, it’s an enunciatory site, and what it tells you – its ‘dimensions, distances and proportions’ – are ‘redefined by the artists according to mythical, psychological or memorial criteria.’1

The suite of videos by Warmun artists Gordan Barney, Betty Carrington, Mabel Juli, Lindsay Malay, Shirley Purdie and Mary Thomas present digitally animated paintings accompanied by narration in each painters’ voice. These lively paintings follow from the regional tradition of narrative painting, which evolved out of the Gurirr Gurirr ceremony developed by Rover Thomas.

The Gurirr Gurirr ceremony came to Rover Thomas in a series of dreams he had just after cyclone Tracey destroyed Darwin in 1974. Gurrir Gurrir is a narrative song and dance cycle in which current, historical and spiritual stories can be disclosed publicly to remember and reinscribe cultural and historical events. Participants carry travelling paintings on their shoulders, animating them with their movements.

By the late 1970s new painting on wood and canvas had emerged out of and beyond the Gurrir Gurrir ceremony.

I was introduced to Rovers’ work and the singularity of East Kimberly narrative painting four years ago, with an image of Hills of Durham, Rover Country (1984). The image was projected onto a whiteboard in a university classroom, surplus light making it appear as though I was seeing it from behind a film of soapy glass.

When Manthia Diawara wrote his text accompanying Friendships: Manthia Diawara Presents the Art of David Hammons at Artspace ‘De 11 Lijnen’ in 2019, he began with: “great artists like David Hammons are always imitating the gestures of the first cave artists, soothsayers, and healers; and in this sense we can say that they are always looking for the first painting.”2 ‘Imitation’ is inflected with intuition and opacity, and in turn the emphasis is on ‘looking for’ across varied sites rather than a specific ‘first painting’.

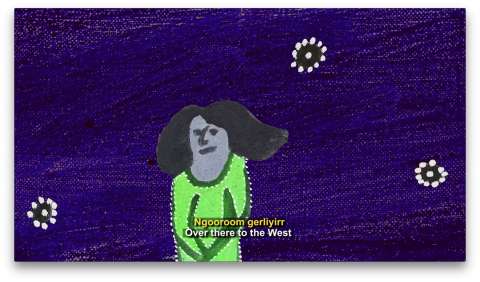

This happens in Betty Carrington’s Garnkiny Marnem (2019), a digitally animated painting with narration by the artist. It’s a painting of an old woman, seen from behind and holding a burning stick toward the moon; a fire between them. I think of the stick: the blushing embers at its tip, glowing like the gold and orange halation that hovers above Wandjinas seen in some Kimberly rock painting.

Introducing her painting, Betty says:

berrema ngarag noonamangge

This is what I made (I made this ~ this is what I painted)

warna-warnarram-berrewa

about the times really long ago

binarrig-garri ngemberramangbe

when they used to teach me

deg-garri noonamanggende

when I used to watch

nyamananim

the old women

Garnkiny

Moon.

She’s instructing the viewer to how the painting (and now animation) reveals and acts out her ancestors’ cosmological gesture, like one of the ‘first painting[s]’ referred to by Manthia.

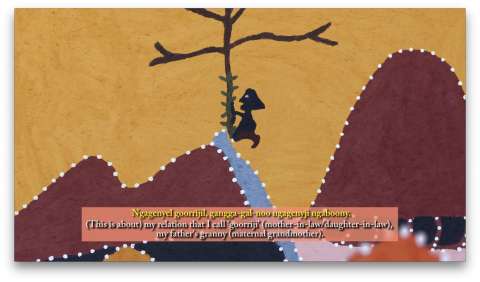

There’s something like this happening in Goorralg – Goorralg (2019) by Shirley Purdie. The artwork tells the story of her granny who sings to a channel-billed cuckoo and willy wagtail as they perch in a tree above her head, asking if they are strangers or countrymen. ‘Goorralg-goorralg’ and ‘jigirrid-jigirrid’ (their natural bird calls) sing back and again, as she sits at the base of a tree digging yams. They’re countrymen and birds, never one undoing the other.

Paintings through time, the land, danced and spoken. Alluvium. Across the Warmun videos, paintings are narrated, but their opacity isn’t stripped away, or reduced for the sake of clarity.

The setting sun pulsing on the horizon. Narrative billows, shakes, dissolves.

Written by Tristen Harwood

Tristen Harwood is an Indigenous writer and critic, a descendent of Numbulwar where the Rose River opens onto the Gulf of Carpentaria.

1 Morvan, Arnaud, ‘The East Kimberley painting movement: performing colonial history’, Australian Aboriginal Anthropology Today: Critical Perspectives from Europe – International Symposium on Australian Aboriginal Anthropology – January 22-24th, 2013

2 Diawara, Manthia, FRIENDSHIPS : MANTHIA DIAWARA PRESENTS THE ART OF DAVID HAMMONS, 2019, https://www.de11lijnen.com/projects/friendships-manthia-diawara-presents-the-art-of-david-hammons

Gordon Barney

Yarrunga (2019)

Digital video with sound, 4 mins 35 sec

© Gordon Barney/Copyright Agency, 2020

Betty Carrington

Garnking Marnem (2019)

Digital video with sound, 2 mins 35 sec

© Betty Carrington/Copyright Agency, 2020

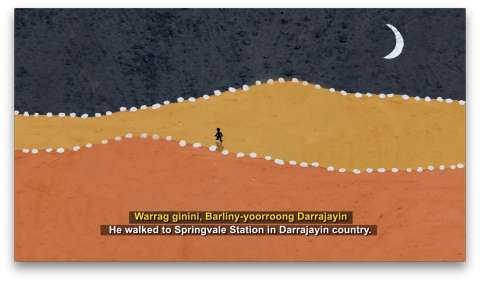

Mabel Juli

My story at Springvale Station (2019)

Digital video with sound, 1 min 55 sec

© Mabel Juli/Copyright Agency, 2020

Shirley Purdie

Goorralg-goorralg (2019)

Digital video with sound, 1 min 52 sec

© Shirley Purdie/Copyright Agency, 2020

Mary Thomas

Yarrunga Healing Water (2019)

Digital video with sound, 2 mins 15 sec

© Mary Thomas/Copyright Agency, 2020

Lindsay Malay

My Grandfather’s Story: Sally Malay (2019)

Digital video with sound, 2 mins 36 sec

© Lindsay Malay/Copyright Agency, 2020

All artists worked in collaboration with animator Bernadette Trench-Thiedeman and sound designer Mark Coles Smith. Original animations were commissioned by the Art Gallery of Western Australia for the Desert River Sea exhibition in Perth (Feb 2019).

More information on Warmun Art Centre can be found here