Ô•diz•m by Avni Dauti & Rebecca Vaughan

With text by Mike Gulliver

HD video, 15 min

Image courtesy of the artists

© Avni Dauti and Rebecca Vaughan

Some 250 years ago, in the French coastal town of La Rochelle, a man by the name of d’Etavigny was wrestling with an apparently insurmountable problem. A successful merchant, he had dedicated his life to building up wealth which he would, normally, have expected to pass on to his only child, a boy named Azy. The problem was that, as things stood, Azy could not inherit. To inherit, the law required him to demonstrate both his lineage and mental competency by verbally stating his identity, and that was something that Azy couldn’t do. He’d never heard his own name. Because he was deaf.

That didn’t mean Azy didn’t know who he was – he knew that very well indeed. From the age of five he had boarded at a local monastery where a number of other deaf people also lived and worked. There, as in other similar situations throughout history that brought deaf people together, a sign language community had emerged and thrived. In their midst, Azy learned to communicate, and read, and write, and think.

No matter how sophisticated Azy’s visual world, however, his father’s problem remained. Inheritance was a hearing-world challenge, one that could only be resolved in the hearing world.

Azy would have to learn to speak…

… or would, at least, have to learn to appear to speak. It wasn’t actually necessary for Azy to understand what he was saying. All he needed to do was accurately produce sounds from a visual cue (‘a’, ‘z’, ‘y’ etc.) that when strung together would, to those soaked in the expectations of the hearing world, appear as an utterance that had meaning.

The specialist skills required to teach Azy to do this – to straddle both visual and sound-based worlds, and to train Azy to produce sound-based evidence (which he couldn’t hear) from visual and tactile cues (which he could feel and see) – were expensive. But the alternative was unthinkable. And so a tutor was employed who worked through touch and vision to teach Azy to produce the sounds of his own name, and of simple French words.

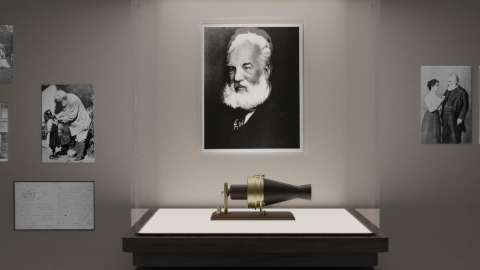

To those unaware of the tutor’s sensory slight-of-hand, Azy’s new ability to ‘speak’ was nothing short of miraculous. The tutor’s success earned him fame, a pension for life from the King, and a nickname, the “Magician of Speech”. It also earned him a string of disciples: fellow ‘magicians’ who worked at the threshold of the senses, and offered evidence – which made sense to those observing – of how they were conquering the ‘deaf condition’ and restoring deaf people to society.

Azy, though, was unimpressed. Almost immediately, he lost interest in producing sounds he couldn’t hear, and again began to seek out people with whom he could actually communicate. He moved to Paris where he re-immersed himself in the visual world – this time joining a large, urban sign language community with links to a wide network of other signers, spread throughout Europe and the expanding world.

Since that point, some 250 years ago, a battle has raged between that global community and the magicians.

On the one hand, deaf people challenge the hearing world to see them not as those requiring the help of experts, or the magic of a ‘cure’, but as those living out a radically different way of ‘being human’: to value their naturally evolved languages, their heritage, history, culture, and traditions, to consider the validity of those expert voices, and wonder at what a ‘visual form of humanity’ offers to our understanding of what, and who we are (and could be) as humans.

On the other, a group of experts, who continue – like Azy’s tutor – to not only persuade the hearing world that they – and they alone – are uniquely qualified to understand and overcome deaf people’s perceived isolation, but also convince some deaf people that, with society now believing that hearingness is within their grasp, that the only valid life choice now open to them is one of ‘passing’ as a hearing person.

Avni and Rebecca’s film shows us a glimpse of that battle. But it also does more. In the light of Azy’s story, and aware now of how we might have unwittingly played into the hands of the magicians by understanding the evidence that they show us only through the lens of our own reality, it asks us how we might take the first steps in a journey that will bring us out of our hearing-only world, and through deaf people’s visual reality, into a deeper understanding of what, and who we, and wider humanity, might become.

Mike Gulliver is a writer and an academic at the University of Bristol, UK.

Ô•diz•m

HD video, 15 min

Images courtesy of the artists

© Avni Dauti and Rebecca Vaughan